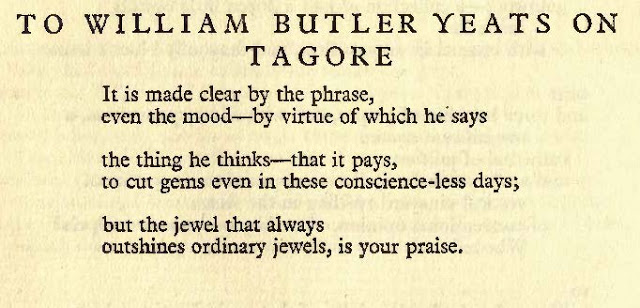

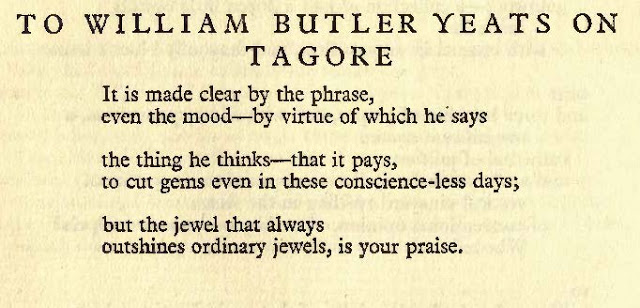

Moore first sent“To William Butler Yeats on Tagore” to a little magazine on November 11, 1914, four days before her 27th birthday.

It appeared in The Egoist of May 1, 1915 and later in Poems, 1921, as above.

Rabindrinath Tagore, a Bengal writer from a distinguished family from Calcutta, translated his Gitanjali or Song Offerings into English for private circulation by the India Society of London in 1912. Macmillan in London picked up the book and published an edition in March, 1913. On November 13, 1913, Tagore received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Key to the Macmillan edition was an enthusiastic introduction by W. B. Yeats. The Irish poet writes: “These lyrics. . . display in their thought a world I have dreamed of all my life long. . . . A tradition, where poetry and religion are the same thing, has passed through the centuries, gathering from learned and unlearned metaphor and emotion, and carried back again to the multitude the thought of the scholar and of the noble. If the civilization of Bengal remains unbroken, if that common mind which—as one divines—runs through all, is not, as with us, broken into a dozen minds that know nothing of each other, something even of what is most subtle in these verses will have come, in a few generations, to the beggar on the roads.” He goes on to compare the poems to the voices of St. Francis and William Blake.

Whether Moore saw a copy of Gitanjali or knew it from reviews, she had enough sense of it to think that Tagore “says / the thing he thinks.”

An example of one of the songs in Gitanjali:

53

Beautiful is thy wristlet, decked with stars and cunningly wrought in myriad-coloured jewels. But more beautiful to me thy sword with its curve of lightning like the outspread wings of the divine bird of Vishnu, perfectly poised in the angry red light of the sunset.

It quivers like the one last response of life in ecstasy of pain at the final stroke of death; it shines like the pure flame of being burning up earthly sense with one fierce flash.

Beautiful is thy wristlet, decked with starry gems; but thy sword, O lord of thunder, is wrought with uttermost beauty, terrible to behold or think of. (p.48)

Frontispiece to Gitanjali, Tagore by William Rothenstein

Following her tribute to Tagore, Moore takes up Yeats’ book of essays, The Cutting of an Agate. She wrote to her mother from Washington, D.C., in March, 1914, that she had read the book at the Library of Congress: “I have never read more earnest fanciful and ennobling prose.” (Leavell, 131) For this poem, she draws on the end of the introduction:

“I have been busy with a single art, that of the theatre, of a small, unpopular theatre; and this art may well seem to practical men, busy with some programme of industrial or political regeneration, of no more account than the shaping of an agate; and yet in the shaping of an agate, whether in the cutting or the making of the design, one discovers, if one have a speculative mind, thoughts that seem important and principles that may be applied to life itself, and certainly if one does not believe so, one is but a poor cutter of so hard a stone.” (New York: Macmillan, 1912, p. vi)

Moore excluded this poem when she published Observations. Tagore’s popularity, immense in England and America in the 1910s when he read to packed gatherings, waned until, “ by 1937, Graham Greene was able to remark, ‘As for Rabindranath Tagore, I cannot believe that anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously.’” (Amartya Sen, “Poetry and Reason: Why Rabindranath Tagore Still Matters,) The New Republic, June 30, 2011. ) Yeats, of course, was another issue and Moore would turn to him repeatedly over the next decade and a half.